HackIM 2016 Case Study

The Dystopian Narwhals played in the HackIM 2016 CTF organised by Nullcon the last weekend and I must say, it was the most controversial ones I’ve ever experienced. In this post, I will briefly describe the competition format, the controversies, and provide an analysis of the overall experience from the point of view of a participant.

The Format

Challenges

The CTF was standard jeopardy style with 8 categories with 4-5 challenges in each category. Here they are with the point weightages:

- Programming (200, 300, 300, 400, 500)

- Cryptography (500, 400, 400, 200, 500)

- Reverse Engineering (100, 300, 500, 500)

- Exploitation (100, 200, 300, 400)

- Miscellaneous (100, 200, 300, 400)

- Web (100, 200, 300, 400, 500)

- Forensics (100, 200, 300, 400, 500)

- Trivia (100, 200, 300, 400)

Now, the titles might be rather misleading for some of the categories. We can better accurately describe them as:

- Programming - Better described as reconnaissance since there was very little programming involved. Most of the challenges involved searching for information on social media. Only Programming 500 could be slightly construed to be a programming challenge.

- Trivia - The challenges were a mish mash of recon and crypto. No knowledge based challenges (except maybe Trivia 300 where a Gravity Falls obsession would have helped) like you would expect of a trivia category.

- Misc - Not exactly a misnomer, but the challenges were a better fit for programming. Most of the pain in the ass challenges came from this category.

There were no breakthrough points given to teams who solved a challenge first.

The challenges did not have a unified specific flag format. There was a really heavy requirement of guessing which strings are flags. The competition did not penalise incorrect flag submissions or required captchas.

Official Communication

The official means of communication with the organisers was through email. However, they did not seem very responsive through this channel.

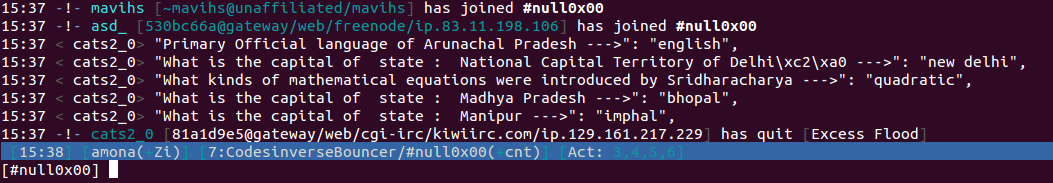

The unofficial means of communication that was given in their rules page was the IRC channel #null0x0 on freenode. There was very little communication from the organisers here as well.

The Controversy

The CTF was fraught with complications from the start, with its history in 2015 colouring the opinions of this year’s participants when they attempted the challenges. According to comments on CTF time, it seemed like prior events were happening again.

The first real issue that came up was the lack of proper flag formats, and the extremely vague and badly worded challenge descriptions. For example, Crypto 1 (worth 500 points) had the following description:

You are in this GAME. A critical mission, and you are surrounded by the

beauties, ready to shed their slik gowns on your beck. On onside your feelings

are pulling you apart and another side you are called by the duty. The biggiest

question is seX OR success? The signals of subconcious mind are not clear,

cryptic. You also have the message of heart which is clear and cryptic. You just

need to use three of them and find whats the clear message of your Mind... What

you must do?

Basically, the challenge requires you to find a cipher text given a plain text

and the corresponding cipher text. This was trivial to do (see the write up in a

following post) but the flag was not apparent. The unknown cipher text decrypted

to

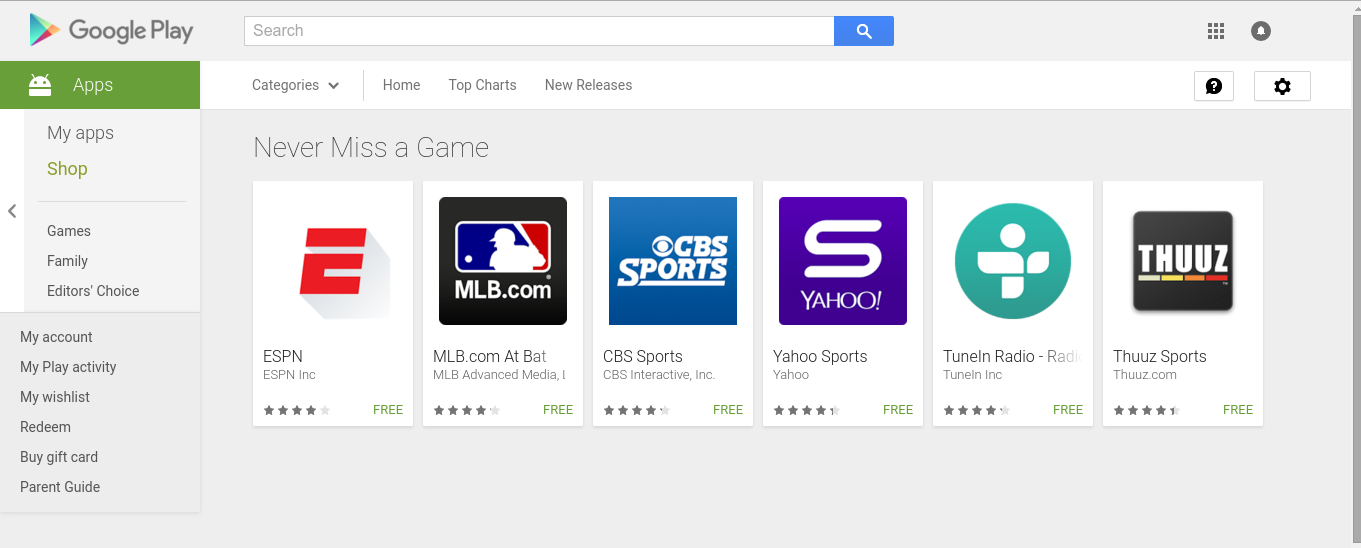

https://play.google.com/store/apps/collection/promotion_3001629_watch_live_games?hl=en\n

and if you followed the link, you’d get the following page:

The flag was ‘Never Miss a Game’. It was not possible to realise that is the flag without extensive guessing.

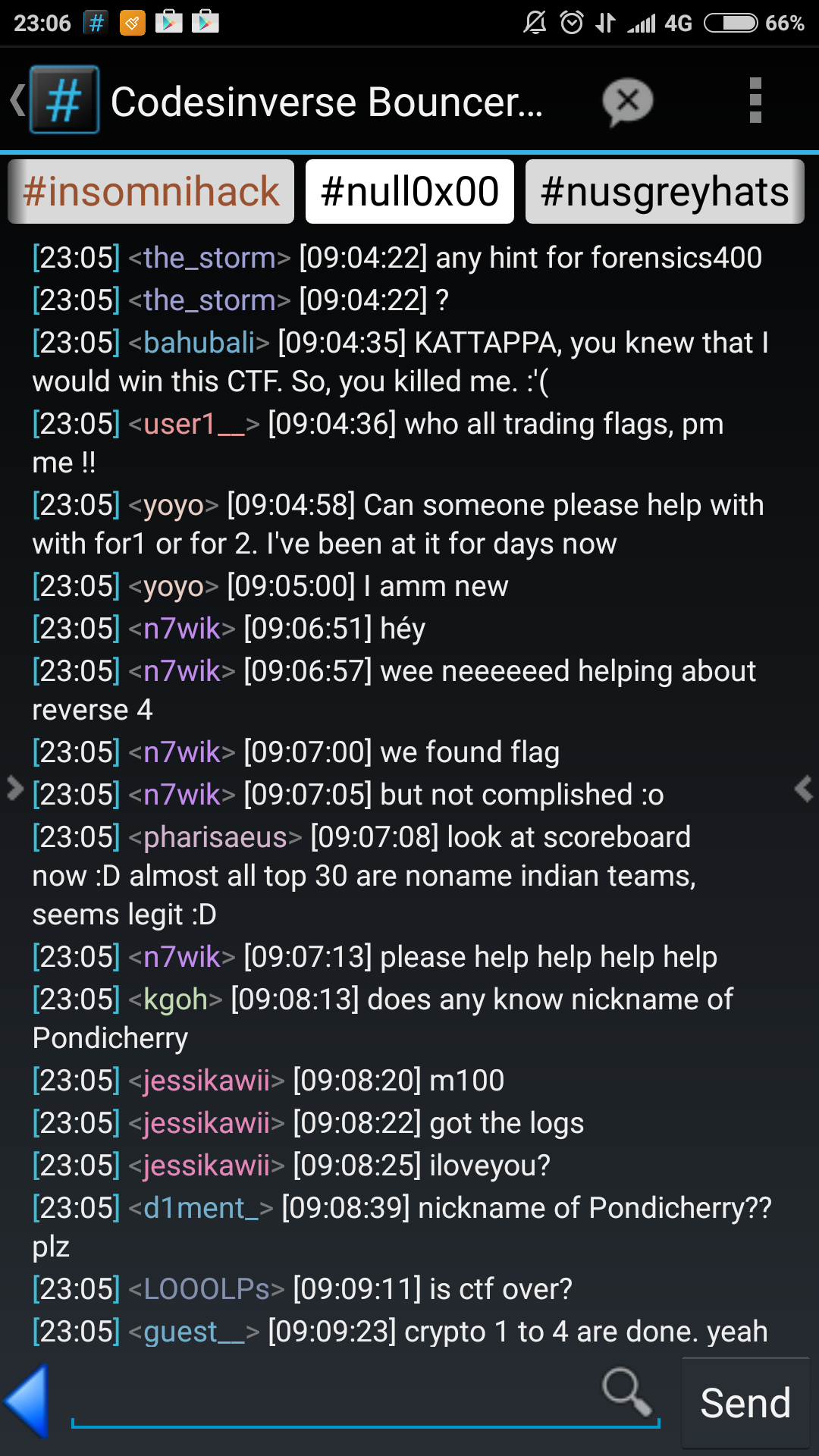

Now, this naturally lead to a lot of people asking for support from an admin or hints on how to proceed. There were no admins on the IRC channel and so people started helping each other because the challenge was just plain ridiculous. This set the precedent for attitudes towards the other challenges.

Another example would be the Know India (Misc 300) challenge where teams had to answer 50 questions on India trivia. The problem here was that certain questions had flawed answers and teams were unable to get those questions right. This eventually lead to a lot of anger and frustration to the point that some people were dumping answers to questions and incessantly asking for the answers outright. A lot of people begged for the flags in private messages.

Web 4 was also another challenge that prompted a lot of confusion from the players. The flag page was printing “Flag:” without anything after. I found out that it was because of the Content-Length header pretty early on but everyone else was livid at getting screwed out of their flag after what should have been a moment of triumph. So there were more requests for admin verification which were largely met with silence from the admins.

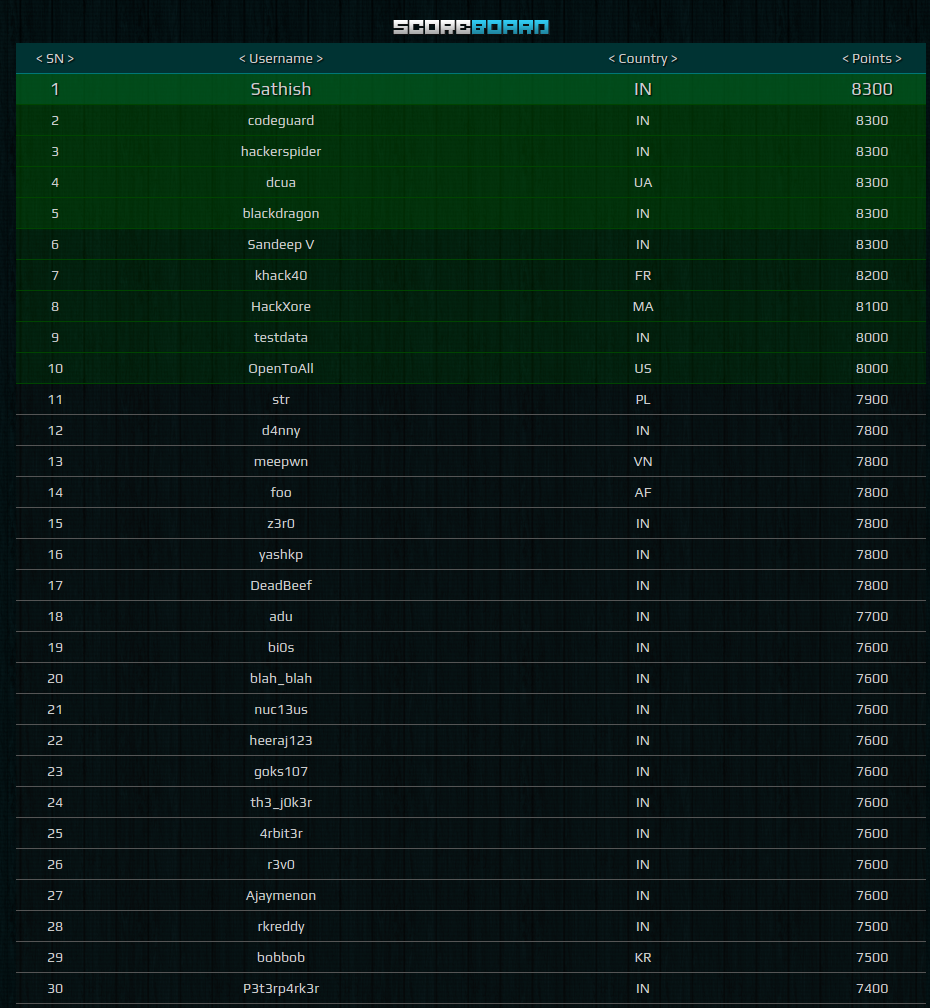

However, the largest controversy happened about 5 hours before the end of the competition. Flag sharing was happening sporadically by then but this was the tipping point that sent certain teams and their affiliates skyrocketing to the top of the leaderboards. The scoreboard was also taken down at this point. No other teams were able to submit flags. Here is a snapshot of the scoreboard near the end of the competition:

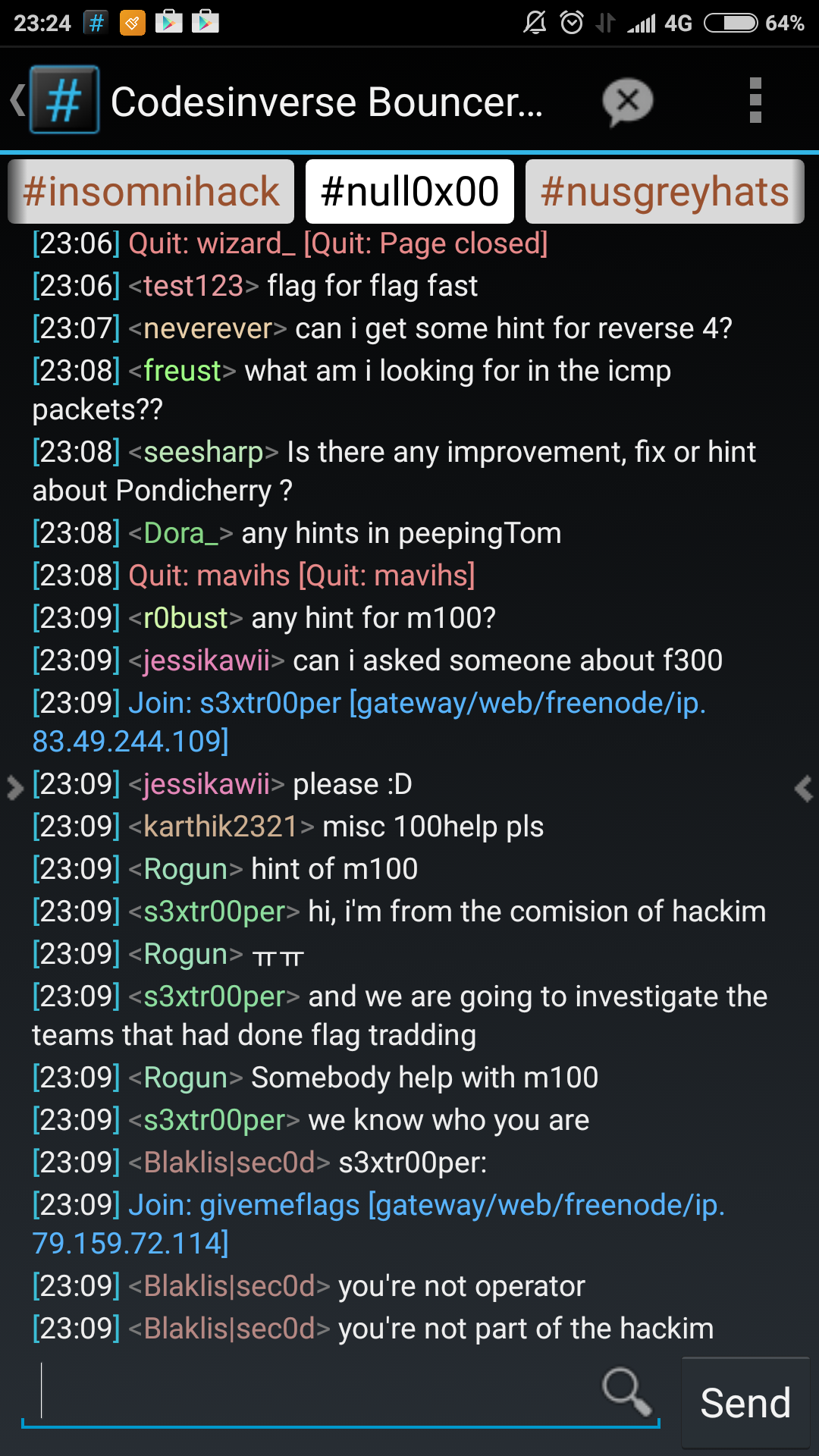

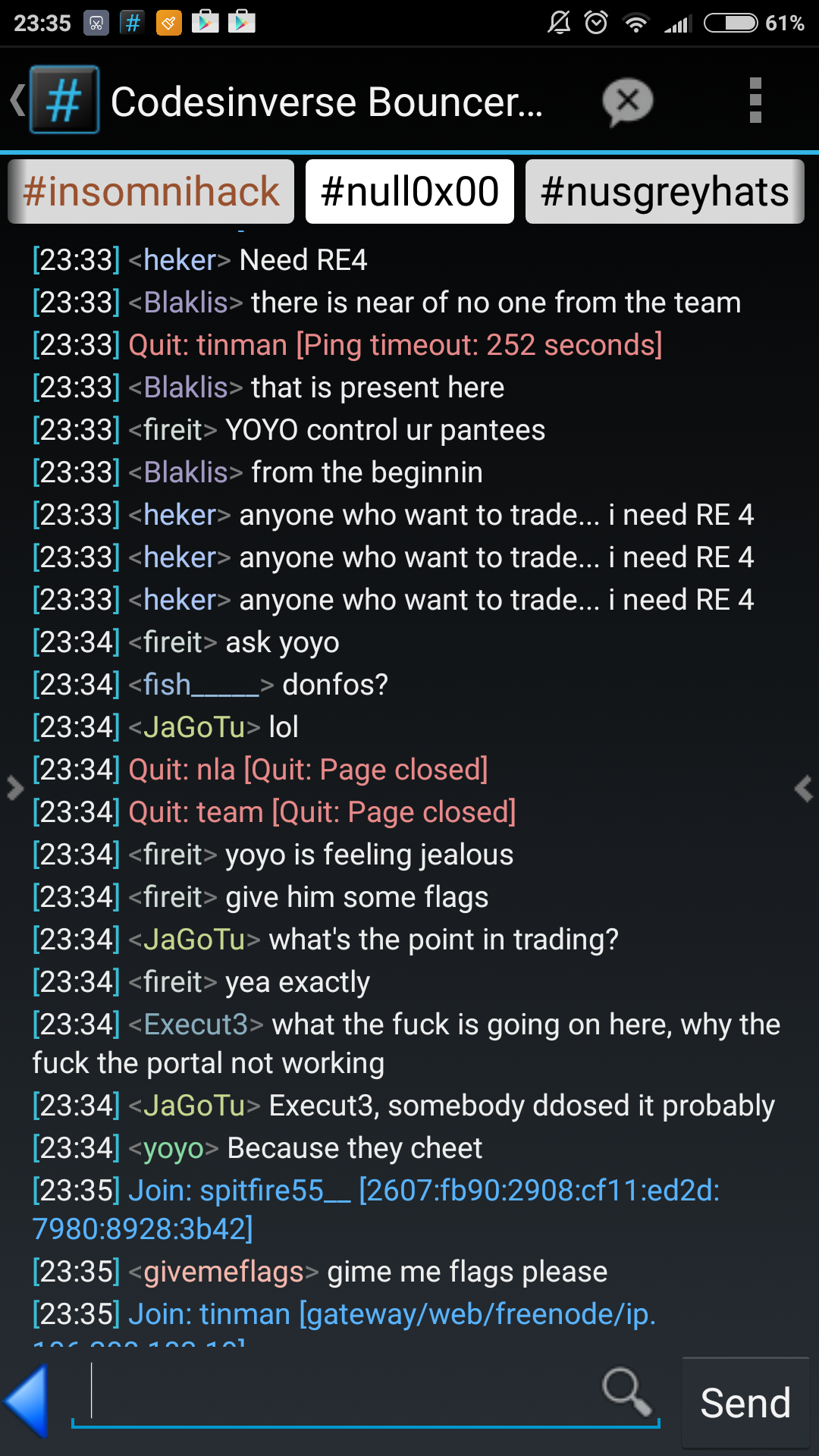

Also, here are some screenshots of the IRC channel during this period:

I am happy to note that the organisers recognised their mistakes and took the effort to clean up the scoreboard though (see the featured image at the top of this post for the final top 15 teams). Congratulations to the winning team, HackXore.

My Analysis

I believe that the current state of affairs stem from the following main points:

- Improper challenge preparation and inconsistency:

- The lack of quality control lead to bad challenge descriptions and bad implementations resulting in extreme ambiguity. This causes an increased requirement for ‘guessing’.

- The lack of a specific flag format. Without a specific flag format, participants are left without a means of verifying that their answers are correct before submission. This is an important point in any CTF. If it is impossible to specify a flag format for a particular challenge, it is better to explicitly say so to prevent contestants swarming the admins.

- The lack of point normalisation. In this case, the exploitation and reverse engineering challenges were disproportionately assigned points when compared to crypto. The easiest group challenge granted 500 points to a solver while the level of skill required to solve the easiest exploitation challenge far exceeds the most difficult of the crypto challenges. This motivates players to ignore the better set challenges.

- The lack of prior testing. Challenge creators should always view a problem from multiple angles and from the point of a view of a person who does not have prior information. This means that if multiple sources online says that the answer to a particular question such as ‘where does River X end?’ is ‘River Y’ it should accept ‘Y River’, ‘Y’, ‘y’, and so on. Also, test for errors or potential confounders such as when a page tells you that a flag is supposed to be printed by it isn’t due to misconfiguration of the application.

- Lack of Official Communication

- Email was the official emails of communication between participants and organisers. This would be acceptable except there seemed to very little response from the organisers during the competition.

- The IRC was the next best thing. However, the admin presence there was negligible.

- With the lack of official correspondence, the less resourceful participants took to the ‘streets’ and requested for information within themselves.

- Lack of Reprisal for Bad Behaviour

- People were begging first for hints, and next for flags. Usually, this sort of behaviour would be immediately quelled with either warnings or a ban from an administrator but once these people realised that the channel was a free-for-all, they conducted their business in the open.

- Some teams created smurf accounts to push other teams out of the top 30 range that grants t-shirt prizes. These teams were not punished at all during the duration of the competition. The fact that prizes were targeted towards single-player teams probably contributed to these greasy decisions.

I see many of the CTFtime comments providing engineered solutions to prevent teams from cheating but it is of my opinion that effective moderation, an in-the-loop administration, and ample official communication are the key aspects to prevent cheating. Ban the offenders early, and you stop it from spreading.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we should not view HackIM 2016 as a waste of time but instead treat it as an important case study for future CTF organisers. There are many lessons to be learnt here, not just for the Nullcon CTF organisation team but for all of us. Also, future CTF organisers should take notice of the teams who were removed during the sanitisation process and perhaps bar them from playing in your CTFs or stop them from claiming prizes if they do not provide in-depth write-ups free from plagarism.

Leave a Comment